ST. JOHN'S, N.L. — When Quebec Premier Francois Legault floated the notion of herd immunity for COVID-19 in April of this year, epidemiologists across the country were flabbergasted.

“The concept of natural immunization does not mean we are going to use children as guinea pigs,” Legault told reporters. “What we are saying is people who are less at risk, people who are under 60, can get a natural immunization and impede the wave.”

Legault later stepped back from his comments, but natural herd immunity has its supporters in the medical community, even though the majority of experts consider it reckless and unprecedented.

The idea is that if a large enough percentage of the population — 60 to 70 per cent in the case of COVID-19 — gets infected, these people will be immune and unable to spread the coronavirus, so the number of cases will begin to drop.

There are several problems with this idea, as will be seen below, but the most obvious is that in most jurisdictions throughout North America, the policy would see hundreds of thousands and even millions of people die before the threshold of herd immunity is reached.

Atlas shrugs

In the United States, the country’s top infectious disease expert, Dr. Anthony Fauci, has been shunned in recent weeks as the White House moved to embrace the advice of a radiologist named Scott Atlas.

Atlas has pushed the idea of letting millions more people catch COVID-19 rather than trying to halt the spread, and has even contended that non-medical face masks don’t work, something that has been clinically proven as false.

He’s had social media posts removed from the platform as fake news, but his ideas have been backed by a group endorsement of “focused protection” issued earlier this month called the Great Barrington Declaration.

Petitions can carry a lot of weight, but the credibility of this one became dubious after Britain’s The Independent found dozens of questionable names in the mix. Among them: “Dr. Person Fakename,” “Dr. Very Dodgy Doctor” and “Dr. Johnny Fartpants.”

Spiral effect

The main problem with the proposal, says a St. John’s clinical researcher, is that natural infection is not what the term herd immunity was originally meant to refer to.

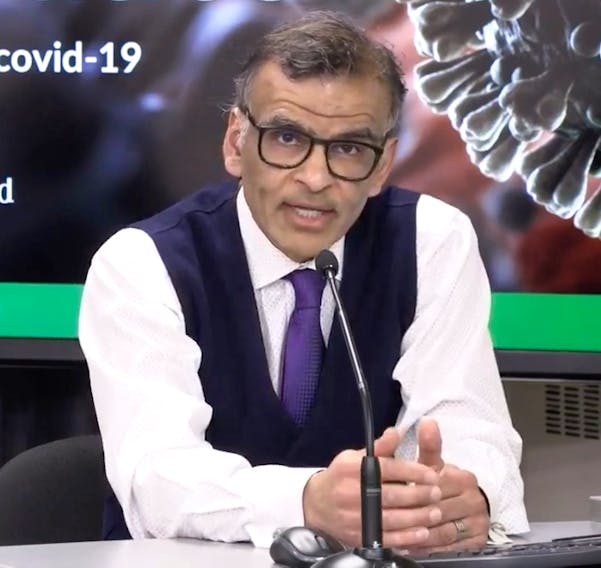

“Herd immunity as a concept is really important, but it’s important in terms of vaccination,” Dr. Proton Rahman told The Telegram last week.

Rahman has been leading a team looking at Newfoundland and Labrador’s statistical vulnerability since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“This issue of herd immunity is attractive for everyone because once you actually get there, you stop generating large outbreaks. That’s the good thing about herd immunity,” he said. “But it can only be safely administered when it’s part of a vaccination program. It’s not desirable or sometimes even possible to achieve herd immunity through natural infection of the population.”

The raw numbers are frightening enough.

It’s estimated the infection fatality rate (IFR) for COVID-19 is between 0.5 and 1.0 per cent. That’s the percentage of people who die from the disease out of all those infected — including those who didn’t show up in confirmed cases.

How do they know that number? Some countries have tested for antibodies and have been able to estimate how many people had an asymptomatic infection and were never tallied in the official count.

Taking 60 per cent of the province’s population — which is what would be required for natural herd immunity — and multiplying it by the IFR, you’d be looking at about 2,000 deaths in Newfoundland and Labrador. And that’s low-balling it.

Then there are the spinoff effects.

“The thing that we don’t think about often enough is … there’s all sorts of long-term consequences from a viral infection,” Rahman said.

Measles, for example, can cause brain damage, hearing loss and immune suppression. It’s already known that COVID-19 can damage the heart, lungs and brain.

Pushing the capacity of the health-care system is also a huge concern.

“What we’re fearful of the most here is actually the non-COVID deaths,” Rahman said.

“In the best-case scenario, we can only clear 40 per cent of the ICU. Sixty per cent of the ICU we need for heart attacks, strokes, urgent surgeries and that kind of stuff. If your system is overwhelmed with COVID, all these treatable things, you can’t manage.”

To top it off, we don’t even know how long immunity from COVID-19 lasts after recovery.

“There’s no firm evidence that you get long-lasting, protective immunity once you have the (coronavirus). Like, once you have the flu, you can get another one the same season,” Rahman said.

“If you’re wrong about that assumption, you go through all this, you go through the deaths, and you’re not even immune to begin with.”

Rahman says turning the idea of herd immunity on its head has been a way for leaders to escape culpability when community spread has gotten out of control, as it has in the U.S.

“That is more of a way of explaining their failure than it is a strategy.”

Peter Jackson is a Local Journalism Initiative reporter covering health for The Telegram