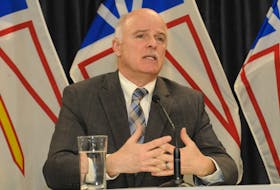

ST. JOHN'S, N.L. — Robin McGrath’s time on the witness stand at his trial ended abruptly Wednesday afternoon, leaving him with a puzzled look on his face.

The 50-year-old elementary school principal spent a day and a half under oath, answering questions related to allegations that he had assaulted and threatened children with special needs at his Conception Bay South school between 2017 and 2018.

Some school staff testified they saw McGrath angrily picking up and slamming down chairs while children were sitting in them, grabbing children by the face and leaning in close to yell at them, physically restraining children, stepping on a child’s hand until the boy cried out in pain and dousing a child with cold water until he vomited. One teacher testified McGrath had asked her for a pair of scissors before holding them up to a child and threatening to “chop (their) fingers off.”

Other staff members have told the court McGrath was appropriately stern when disciplining children, and never abusive or intimidating.

At times speaking emphatically and referring to himself in the third person, McGrath refuted the allegations. In some cases he insisted incidents of appropriate discipline had been misconstrued, while he said others simply never happened.

The principal testified he had only ever lifted the front of a child’s chair in order to move it over his foot as he was turning it toward him, lightly touched children by the face in an effort to redirect their focus toward him, used cold water on a child’s hands as a sensory strategy and restrained children only with the type of hold he had learned in his school district-approved crisis prevention intervention training in extreme circumstances.

McGrath acknowledged he had commented to a teacher, “What happens in (a specific classroom) stays in (the classroom), we’re like the Mafia here,” but said it wasn't about keeping anyone quiet about mistreatment of children.

“I absolutely did say it, yes,” he testified, calling the remark a "lighthearted reminder" to protect the dignity of a child with special needs. “Staff were given the very serious instruction that (the child’s) business was (the child’s) business.

As for the allegation involving the scissors, McGrath said he had spoken to the child as a warning, not a threat. The boy had been attempting to injure himself with scissors, McGrath explained.

“I said, get out of that before you chop the hands off yourself. That’s what happened,” he told the court, adding he’d say the same thing to his own child in a similar circumstance. “My response wouldn’t be, oh honey, that’s dangerous, put that away, you could cut yourself. My Robin McGrath response would be, get out of that before you chop the hands off yourself. That’s how I talk.”

On cross-examination, prosecutor Shawn Patten questioned McGrath on why he would have to raise a child’s chair at all if he was turning it to face him.

“Wouldn’t it make more sense to move your foot?” Patten asked.

McGrath attempted to demonstrate then said, “Sir, all I can tell you is this is something I’ve done my entire career. Is it something that could have been done a different way? I guess it could. It’s how I’ve done it, it’s never been an issue."

Patten suggested McGrath had lifted the chairs to jolt and scare the students.

“I suggest … a young child would then be afraid and listen to what you had to say out of fear, isn’t that correct?” Patten continued.

“I would disagree with you,” McGrath replied, saying his purpose was to speak to students, not cause them to be afraid of him. “The way that you’re explaining is just not accurate. Any meeting for a child is not for Robin McGrath. It’s for the child.”

“It depends on the conversation and I guess to some extent to the comfort level of the child. Yes, I have had my hand on children’s face to direct their attention. If I’m talking to them, I might hold their face.”

“Fear, especially in children with exceptionalities, can cause some level of compliance, would you agree?” Patten asked.

“I wouldn’t know,” said McGrath.

Patten questioned McGrath on why he touched children’s faces in any case.

“In general when children come to your office, do you take their face to speak with them?” the prosecutor asked.

“It depends on the conversation and I guess to some extent to the comfort level of the child,” McGrath answered. “Yes, I have had my hand on children’s face to direct their attention. If I’m talking to them, I might hold their face.”

“None of them required to be touched by you. They can listen to you,” Patten suggested.

When McGrath spoke of touching another boy on the face, head and shoulders after disciplining him, Patten submitted, “That’s an additional thing you do to put a bit of fear in them. You touch them.”

“I’ve already clarified," McGrath replied. "Mr. Patten, if I can say so, putting fear in children doesn’t work.”

Patten suggested McGrath had felt pressure from the school district to be inclusive of children with special needs, pointing to.a memo the district had sent to administrators at the start of the school year encouraging all children to attend class the first day.

“You took the letter from (the district) as a challenge, didn’t you? You wanted those children with exceptionalities to be there at any cost,” Patten suggested, even if it meant McGrath physically removing a child from a vehicle.

Since the school had the resources to accommodate children with special needs, anything less would be “a failure on my part,” McGrath said.

“Exactly,” said Patten.

The prosecutor ended his cross-examination by telling the court he had no further questions.

Testimony in McGrath’s trial has concluded. The matter will be called again in provincial court on Nov. 9, when the court will deal with an application made by the Crown before lawyers make their final arguments.

Tara Bradbury reports on justice and the courts in St. John's.