ST. JOHN'S, N.L. — In 1994, Jeik Kalunga Loksa and his four young children were on Lake Tanganyika, stuck on a boat floating between the borders of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Tanzania, Burundi and Zambia.

For the third time in his life, Jeik was escaping the DRC. He had arrived there with his four children after fleeing Egypt because of rising political and religious tensions. He had worked in Egypt for 12 years as a musician. Loksa — not his family name — is a stage name he adopted there. As a Roman Catholic, he feared for his and his children’s lives.

From the DRC, he wanted to travel north to Kigali, Rwanda, but a Roman Catholic bishop told him he would be killed — the Rwandan genocide was unfolding.

The bishop suggested they take a boat to Tanzania.

“But Tanzania rejected me already when I was crossing with Air France from Egypt, they rejected me at the airport,” Jeik said. “(The bishop) told me, 'Just take a chance.’”

But the Tanzanian authorities rejected his application again and they had to stay on the boat.

“We stayed 12 days (and) by that time my children started (passing) blood,” he said. “It was bad, because we had no water to drink. … People were going out, but me and my family (had to stay).”

In desperation, he cleaned up his children and showed an immigration officer a piece of paper with his children’s blood on it.

“She had empathy, she was a nice person,” Jeik said. “She gave me a token (to show immigration officials), but she advised me, ‘Don’t look left or right, just go straight (and) get your children some medication.’

“When I went out, it’s like taking a fish and putting it back in the sea — I ran.”

He ran to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) office in Kigoma, Tanzania.

“I went there, I presented some documents I had from Egypt, I explained everything to a protection officer, and he came with me, he said, ‘Let’s go, where are your family?’” Jeik said. “He put us in a small hostel.”

From there, the family spent six years in a Tanzanian refugee camp before arriving in Canada.

It was in that camp where the memories begin for Jeik’s son, Mponda Kalunga. He was five years old at the time.

“All my memories of who I am are from that time,” Mponda said. “Those memories that form you when you’re a kid, they’re from that time.

“I remember the community, the friendships that I had with my little friends. I remember hanging around, going in the woods, hunting with the elders.”

Though he was surrounded by poverty and suffering, “you don’t realize it’s suffering until you see something better,” he said.

He recognizes the hardships now, but still, it’s mostly the good he remembers.

“I never feel like I’m a man. I still feel like a little kid in that camp.”

“Inside, you know, you always feel like a little kid when you were, like, eight,” he said. “I never feel like I’m a man. I still feel like a little kid in that camp.”

His father would leave for months at a time, trying to find ways to get them out. During those times, they would stay with others in the camp.

Finally, the family was accepted as refugees into Canada in 1999.

“You go from Africa, and you hear about this place Canada, they call it … ‘Heaven,’” Mponda said. “Then we finally get here and it’s freezing, man. … It’s so cold it frightens you.”

Not knowing English, 10-year-old Mponda relied heavily on body language to navigate social interactions.

“Early on, I had to detect those things,” he said. “I could tell from body language, from somebody’s eyes … if they liked me, if they didn’t like me.”

His life became easier when he started boxing in his teenage years, he said. And looking at it now, he believes having to concentrate on body language gave him the edge that helped him become successful in the sport.

“I went to the Canada Games after about nine fights and I got silver medal,” he said.

That was in 2007. Now, at 31, he’s living in Toronto, signed with a boxing promoter, and is boxing his way up the ranks.

But his father’s love of music and art must have rubbed off on him, as he’s a passionate songwriter and painter as well.

“What (my father) is doing, he’s actually a mastermind,” Mponda said. “Even though he can’t play all those instruments, the music is in his head, the music is in his heart. … It will keep him alive a long time, because he still feels like he has something to live for. That’s the point of the music — he has life. Music is his life. Music is literally his life.”

In the 1950s, all over the city of Bukavu in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, audio speakers attached to large poles blasted music, Jeik Kalunga Loksa recalls.

“You could hear them all over the city, and when you walk, you feel like dancing,” he said.

Jeik was born in Angola in 1943, and his father moved the family to the DRC when he was very young.

Like many kids, he loved making up games.

“I always stayed in my mother’s kitchen and I always feel the urge of finding sounds,” Jeik said.

He would fill glasses with different levels of water and hit them with a fork.

“If I didn’t get the sound I want, I break the glass,” Jeik said, laughing.

“When you’re on stage … you have to become wild."

In 1961, not long after the country became independent, Jeik left the DRC for the first time. He was 17 and described the situation as chaotic.

“Those Congolese rebels … they even killed priests,” he said. “That was completely against my mind.”

After two years in Uganda, Jeik moved to Nairobi, Kenya. It was there that the games he played as a kid in his mother’s kitchen would begin paying off.

In 1963, he started a band with some local boys from the streets, he said. They called it Air Fiesta Matata, but eventually shortened the name to Matata.

Jeik was not only a singer and dancer, but a composer as well, despite his voice being his only instrument.

“I always wake up and feel like whistling,” he said. “And when I whistle a tune, that’s my way and musicians have to listen to what I’m telling them.”

Even in casual conversation, Jeik breaks into a melody or rhythm, imitating instruments to describe music.

In the early ’70s, a song Jeik wrote about his childhood, “Tango Ya Bomwana,” was entered into a competition by the BBC World Service. Matata won and was invited to London, England, to pick up the prize of £125,000 and a Vox guitar.

They also played a few concerts to screaming audiences, Jeik said.

“When you’re on stage … you have to become wild,” Jeik said. “That’s what made Matata famous because every time we’re on stage people have to turn and say ‘Wow. What is going on with those guys?’”

Before long, they were signed to President Records. They recorded two albums and toured Europe multiple times.

But members of the band started missing their families, and they split in 1974 after a tour of Asia. Jeik remained in London.

Being fluent in French, he worked at the BBC as a French announcer for three months, and formed a new group called Songi Songi.

“In Congolese language, songi songi means gossip,” he explained.

It worked for about six months, but Jeik and the other band members, who were from Jamaica, argued over their habit of smoking marijuana on stage.

“At that time I smoked marijuana, too, but smoking on stage (I was) completely against,” he said.

In 1980, after 19 years abroad, he returned to the DRC and searched for his family. But the situation there had changed, and not having spoken to them since he left, he could only wonder where they had gone.

The soldiers in the city of Kinshasa would look for bribes in return for a person’s safety. They took notice of the sharply dressed man with the foreign currency.

“Soldiers became close to me, they wanted to know, who is that guy?” Jeik said.

He had to leave again.

•••

He ended up in Cairo, where he put together a group, adopted the stage name “Jeik Loksa” and auditioned to play at a casino.

After his audition, the owner called him over for a drink and some lamb chops.

“I ate, I drank my whisky, then I told him I was tired, I wanted to go back to the hotel,” Jeik said.

The owner said he would give them the contract, but he wanted Jeik to stay to watch the belly dancers.

"Do you know belly dancing?" Jeik asked during the interview with The Telegram. He makes a "chic-a-chic, chic-a-chic" sound to mimic the rhythm before continuing.

“After watching them … on my way out, one of the belly dancers touched my shoulders, she came running behind me, she just said, ‘You’re my husband,’” Jeik said. “Three days later, she married me.”

Her name was Karima Thabet Abd El Kerim Khalifa and she was known all over Egypt for her dancing, Jeik says. The couple had four children together — Anna, Louise, Marina and Mponda, their only boy.

After 12 years, the atmosphere in Egypt was noticeably different. Terrorism was on the rise, and some people were adopting a more radical view of Islam. Jeik said foreigners and Christians like him didn’t feel welcome anymore.

The couple planned to leave, but before they could, an immigration officer noticed something about Jeik’s wife. Her documents said she was Muslim, but a small cross tattooed on her right hand, put there when she converted to Christianity, made him furious. She had left Islam; she was considered an apostate.

“They refused to give her her passport,” Jeik said. “They told her she was lucky she wasn’t killed because of that cross. The guy was shouting in Arabic, calling me, my wife and my children dogs and ‘Kill them!’ Oh, it was very scary.”

Jeik ended up having to bribe officials to get his children’s birth certificates. But his wife had to stay in Egypt.

He hasn’t seen or heard from her since, but Jeik believes her family must have hidden her from the authorities to protect her from death.

•••

In 1999, after six years in a Tanzanian refugee camp, the Kalunga family was accepted into Canada, and made their home in St. John’s.

In the early 2000s, Jeik met Curtis and Duane Andrews, two brothers and local musicians.

Shortly after their first meeting, they formed the band Mopaya with several other local musicians, including Bill Brennan, Aneirin Thomas, Alix Maboussou, Natacha Lembe and Jeik’s daughter, Anna. Soon after, Luke Power replaced Brennan.

“(Mopaya) means foreigner,” Jeik said. “Because I’ve travelled all over the world, I’m a foreigner everywhere.”

It was at this time that Jeik, after almost 40 years in the music industry, decided to begin playing the guitar.

Curtis Andrews, who now lives in Vancouver, said Jeik is one of the most fascinating people and musicians he’s ever met in his life.

“His life story should be made into a movie,” he said.

Curtis loves the music they made. And he’ll never forget their time playing together, especially one show in particular.

“He started the song, and he turned around to me and he gave me this look,” Curtis recalls. “Then he just … laid down on the floor and we were like, ‘Holy moly!’ and we called the ambulance.”

It turned out to be heat stroke. But within a week, Jeik was ready to get back on stage.

“Jeik — he’ll outlive a lot of us,” Curtis said. “He’s a survivor, for sure.”

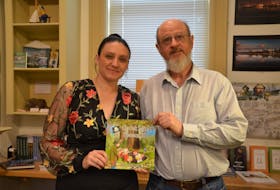

Jeik’s current band, Katapa, was started in 2015 with Craig Penney on lead guitar, Tony Tucker on drums, Aneirin Thomas on bass, Chanel Rolle on vocals and Jeik on rhythm guitar and vocals.

The group played for the Folk Festival 2020 Digital Edition. Jeik is now writing songs for a new album.

@AndrewLWaterman