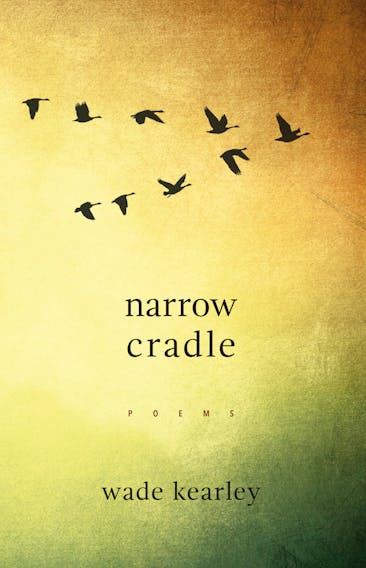

Narrow Cradle

By Wade Kearley

Breakwater Books

$19.95 108 pages

The poems in Wade Kearley’s new volume are divided into 12 sections, organized by calendar months, December to November, all sub-headed “on Lawlor’s Brook.”

They are largely narrative, even in a sense narrated: “I watch the / same street from the same café where … I last saw you, my daughter”; “I used to wish you could fly, / soar over the many who never looked in your eyes.”

The formats shift, from calibrated line breaks, to the introduction of textual beats (or breaths), to the inclusion of back-and-forth dialogues, to the organization of word and line into shapes that take flight from a perch (as in“–American goldfinch” where “the bird, stunned by the falling, / plays dead for the giant who crouches / and exhales a cloud of pity”) or surface through the ocean (like the squid in “il cauto” who “jets away from her squad / her three hearts all pumping copper blood, / then she darts through my breath as it worries upward”). Some are set into three- or four-line stanzas, while others play across single lines and/or paragraphs; “–starlings” is near haiku-weight at just 15 words long.

There’s also some musical composition, in “–amy chains”, with melody from Tamsyn Russell.

Consumed in batches, they exude a diary/journal kind of flavour, nicely in keeping with the chronological unfolding. It’s a year in the mid-life of a poet both dodging and confronting basic significant human issues; the shade of mortality, the joys and fears that bloom and trail from children and grandchildren.

Kearley is concerned with a trio of spheres, or worlds: the natural (through observing the flora and creatures around him); the global (through travel — besides his poetry Kearley has published two travel books, inspired by his 900-kilometre walk following Newfoundland’s abandoned railway); and the internal (arenas that are often turbulent to the point of psychiatric intervention).

Moods range, spirits shift, as images ebb and flow on the pages.

The first few poems are a little pedestrian — though one is set during an air mishap over the Himalayas — but as we read on, they accumulate pitch and punch like a rolling snowball. For example, the counter-puncture of “–shem meditates / on his disease” (according to the Old Testament, Shem was one of the sons of Noah, and his lineage led to Abraham): “There is nobody in the water. // I listen to their splashing. / No one sings to me anymore. // And the songs rend my heart. / I know we are close because we never touch. // All this is / true, because it never happened …”

Many pieces reference or are dedicated to friends, and the delightful “–inbetween” is a “found poem” from an acquaintance’s email: “Xmas come and gone, / New Year’s Eve next. / No plans for me. / Stone Jug restaurant is having a do, / but expensive, and I don’t know people going. // All good so far. No resolutions, per se …” Others are addressed to “you,” sometimes further distinguished as a family member, sometimes not, as in “–the divorce of aurora borealis”; “At dawn a herd of caribou stampedes / across the tattooed slope of your left thigh / as you kick me from under the woolen blanker. // You yawn and gather the folds. / With your arm newly etched in fire, / you banish me. You remind me how / last night I failed you when I refused / to dance beneath the North Star.”

The title is from “May on Lawlor’s Brook”: “We who inherit this narrow cradle herd / Our own broods along the gravel and fret / That time has not yet revealed the threat / That might steal them from us without a word.”

There’s the domestic lull of “–tea & bread rising” “I // Sugar and yeast, water and flour. Salt / spilled on the counter. After a night / of baking, the stove / purrs quiet with birch embers. // I linger in the dawn and break the first crust, / drain the pot. There is time / before I must leave. I lift the sash and whistle / for the finch in the gooseberry bush.”

Contrast that with “–full moon over wreck cove”: “I crouch among the thick alders, halfway up the hill and, / protected from the north winds, / watch broken surf asit scrambles over itself / in the gut, tears away at the seams. / I button my swileskin and wonder, / Am I unravelling too? / Why do I deserve this dream?”

Moods range, spirits shift, as images ebb and flow on the pages.

Joan Sullivan is editor of Newfoundland Quarterly magazine. She reviews both fiction and non-fiction for The Telegram.