With COVID-19 affecting all of our lives, there have been natural comparisons to the 1918 influenza pandemic and its impact on Cape Breton Island.

In the early 20th century, infectious diseases were prevalent in all counties of Cape Breton. Unfortunately, outbreaks of measles, smallpox, diphtheria and tuberculosis along with other illnesses were quite common.

Population explosions around the turn of the century in industrial communities led to public health advocacy for improved sanitary conditions, vaccination programs and infrastructure such as better plumbing and sewage systems.

As a result, when influenza arrived in the fall of 1918, some policies and practices around controlling the spread of infectious disease had already been in place, such as quarantines and restricted public gatherings. This allowed the public health leadership in Nova Scotia to offer a relatively efficient and organized response.

Archival records like those held at the Beaton Institute on the Cape Breton University campus, offer insight into individual and collective actions to catastrophic events.

Instead of multiple social media and broadcast platforms available today, municipal meeting minutes and newspaper articles were the main communication channels.

Municipal annual reports also contain valuable summary information detailing the types of diseases, number of deaths and annual health trends. While statistical information is fairly easy to find, emotional reactions and insight into the human experience are not as common. However, in records related to the 1918 influenza epidemic, the praise for health-care workers is notable.

In Glace Bay, over a span of four months, the town suffered approximately 3,000 cases of influenza and 57 deaths.

In the 1918 annual report, medical officer D. McNeil writes that, “too much credit cannot be given to our hospitals for the manner in which they accommodated the large number admitted, and I do not hesitate to say that they were a great factor in keeping the mortality rate so low when we compare it with other towns of the same population.”

As with the stories we’re seeing today, health-care workers are accepting risks in order to care for others, and to help stop the spread of the illness. To fully grasp past sacrifice and courage exhibited by individuals during times of crisis, more than one archival source is often needed.

For example, Wayne MacVicar’s compilation of vital statistics lists a single obituary entry for a 47-year-old Glace Bay woman, J.C. Cadegan, who died at Marble Mountain. After further investigation using newspaper articles, you learn that Julie Cadegan had been a tireless volunteer nurse in the United States, Sydney, and finally travelled to Inverness County due to a high volume of cases.

She died a few days before Christmas 1918 after contracting influenza.

In the Sydney Record, she is remembered as “one of the most skillful nurses in the province and was a woman of broad sympathy.” Health-care professionals travelled all over the province to where they were needed most, including doctors who provided relief for sick colleagues in North Sydney at the end of 1918.

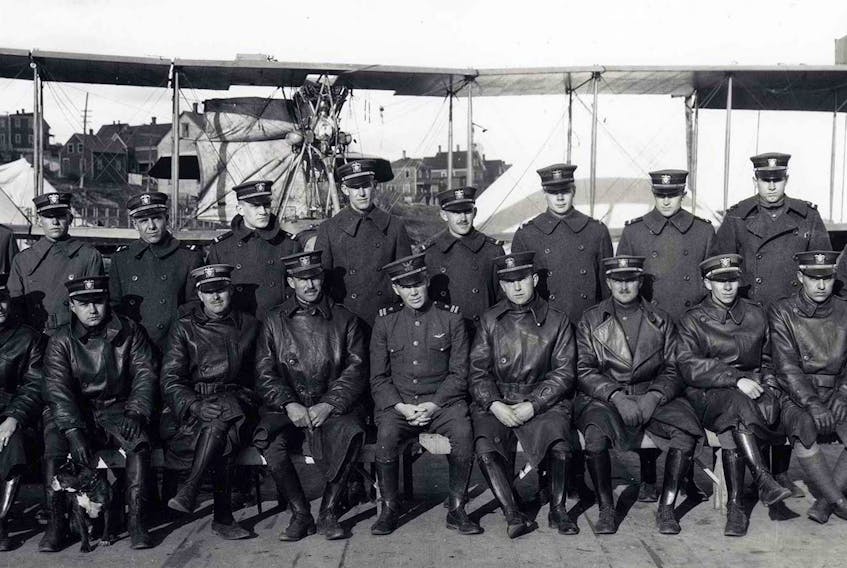

At the request of the Canadian government, a United States Naval Air Station was established to assist with refuelling seaplanes and coastal surveillance. Unfortunately, the flu outbreak affected dozens of servicemen. Gratitude for the care received during the epidemic is noted in the final farewell issue of “Flight,” an internally produced magazine for the personnel at the North Sydney Naval Air Station.

The editors write, “No sort of a story of this station and its experiences would be complete without a tribute to the faithful and heroic work of the Hospital Corps during the epidemic of Influenza. Dr. Caldwell had the misfortune to go down with it himself early in the attack. A relief from Halifax, Dr. Tindall, did splendid service until he too went down with the same disease.”

To learn more about the naval air station, visit the Beaton Institute Digital Archive: https://beatoninstitute.com/north-sydney-flight-farewell-issue.

A century ago, following public health directives and through efforts of dedicated professionals, life in Cape Breton slowly returned to normal. Historical records document a moment in time and can provide insight into actions and outcomes during significant events. More importantly, the records confirm and provide reassurance that despite extreme loss and grief there will be an end to the crisis.

We encourage the public to record their own experiences during this extraordinary time. We want future researchers to know the story of Cape Breton in 2020, and how we cared for and consoled each other and how our community worked together to bring an end to isolation.

While the physical archive is closed, we do encourage you to explore online resources through beatoninstitute.com. You can also reach out to staff via email at [email protected]. We are here to help while you are “research distancing” and intend to provide online tools to help better navigate our digital resources in coming weeks.

Jane Arnold is an archivist at the Beaton Institute at Cape Breton University. She also volunteers with the Council of Nova Scotia Archives and is a board member with Heritage Cape Breton Connection.