Any article on David Woods is automatically going to refer to him as a multi-talented member of Nova Scotia’s arts community.

Playwright, producer, poet, historian, artist and educator are just some of the roles he’s undertaken, sometimes simultaneously. But it’s his current and ongoing mission to raise the profile of East Coast African-Canadian art that’s recently put him in the national spotlight.

“I’ve always been multi. That’s not a normal thing, that’s a childhood damage thing,” says Woods, who spent his teenage years in Dartmouth finding an escape in books and mastering numerous different subjects at the behest of an uncle who constantly challenged him to broaden his mind and perspective.

“If I wanted to have a drama, I just wrote one. I had no idea until other people told me, ‘Hey you’re brilliant!’ I just thought, ‘Really?’ But it wasn’t this thing where I thought I’d try to knock off all these things.”

Shining a Light

In the past month, Woods has been featured in major profiles in the national magazines Canadian Art and Studio - Craft and Design in Canada. They focus on his role as an African Canadian art historian and curator and his involvement with African Nova Scotian quilters and the evolution of a centuries-old form of creation and expression.

On the East Coast, Woods efforts are well-known, since he started the Black Artists Network of Nova Scotia and co-created the landmark In This Place exhibition in the 1990s, and presented exhibitions of Black art at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia in the 2000s.

His work has come to wider attention since he took part in the inaugural Black Curators Forum in Toronto in October, 2019, where he joined around 20 others in his field to address the need for greater diversity in galleries and the broader discussion about historic and contemporary art in general.

“I’m not known in the upper Canadian world of art, but I attended this curator’s meeting and I guess they found what I had to say was intriguing, because they’ve been calling me for all kinds of things ever since,” says Woods.

Black art deserves a prominent spotlight

In a December Canadian Art article on the forum, he expressed his dismay at the lack of Black art in prominent galleries like the National Gallery of Canada, underlining the reason for the founding of BANNS in 1992, and Woods’ current effort to foster a similar group for New Brunswick artists.

BANNS’ artist roster is a diverse one, including creators like painter Letitia Fraser, woodcarver and painter Angel Gannon and ceramicist Julian Covey, who became the first African Nova Scotian board president of Visual Arts Nova Scotia in 2019.

With major exhibitions currently in the works, on African Canadian artist Edward Mitchell Bannister and The Secret Codes’ examination of the connection between quilting and the Underground Railroad, Woods sees the two magazine pieces as bringing significant attention to work that should have been recognized long ago.

“They certainly make people aware of things they’re not aware of. The Canadian Art piece talks about a Canadian artist who became very prominent in the United States, and is almost completely unknown in the country of his birth,” says Woods, referring to St. Andrews, N.B. native Bannister, whose work flourished in the mid-to-late 1800s.

“Which is kind of incredible, because our art historians apparently did not want to bless him with any kind of elevation. Mind you, I think he might have been the first Canadian to win a major art prize in North America, while being Black in the period right after slavery ended, none of that seemed to have mattered.”

Breaking new ground

As underlined by the Canadian Art piece by Kelsey Adams, In This Place at the Anna Leonowens Gallery in 1998 was a pivotal moment, as it highlighted contemporary and folkloric African Nova Scotian art in a way that hadn’t been done before locally.

Informed by Woods’ months of visiting communities around the province, In This Place was also fueled in part by the frustration over the general indifference that greeted African-Canadian art at the time, or seeing exhibits only during Black History Month.

“I think that was very instrumental for why my brain switched into another kind of wanting,” says Woods, who was also conscious in 1998 of the approaching millennium and the major art shows accompanying it.

“And none of them had anything to do with the Black community. So the combination of those two things ... one pissed me off and the other inspired me.

“But then I began to say to myself that it would be nice to have something more than just another Black History Month show, and have a statement.”

Looking back to that 1998 provincial quest for In This Place, Woods says it was as much for his own purposes as it was for the show, to expand the concept of what constitutes African Nova Scotian art and truly represent the community in a broader sense.

“100 years of tradition being unfolded”

“I drove around to communities, just basically asking people. Because there hadn’t been a precedent; it wasn’t like you could go somewhere and find a collection of Black art, or books or any prior knowledge or the internet or anything like that,” says Woods, who’s currently working on a book with Dr. Harold Pearse, charting the work that BANNS has championed and brought to light over the past three decades.

“I took advantage of the fact I knew people in every community, I could show up and someone could guide me or give me a place to stay for the night. And it’s taken me years to understand that we had literally gone from not having art to 100 years of tradition being unfolded.”

Part of that tradition was the quilting that Woods says he hadn’t even considered until a woman from North Preston suggested he look into its importance in Nova Scotia’s Black communities.

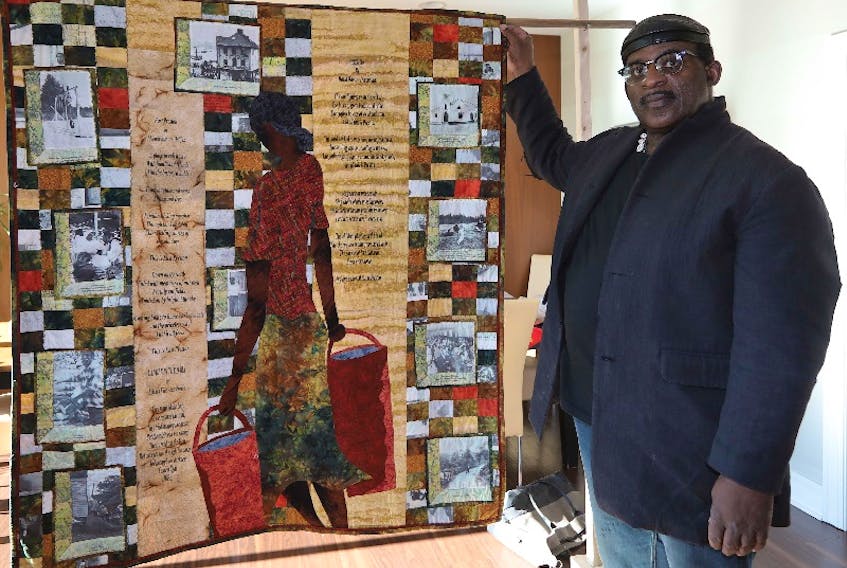

What he found was a practice that was both widespread and unique from place to place, and he ultimately collaborated with Myla Borden from the Vale Quilters of New Glasgow to create a quilt that captured the theme of In This Place.

“It began to show that you could actually embrace your Black culture and history in a quilt, which was not a thing then. Quilts were not seen in that way; you made a quilt pattern, you did it the best you can and then you show it off,” says Woods, who went on to present the first African-Nova Scotian quilt show When Black Women Used to Fly.

The Secret Codes combines the present and the past

Then in 2012, the exhibit The Secret Codes, inspired by the use of quilts to provide secret messages for those escaping slavery via the Underground Railroad, debuted in 2012 at the Quilt Canada Conference in Halifax.

Nearly a decade later, The Secret Codes will return for an exhibit in Charlottetown in 2021 which Woods plans to tour to other galleries in Canada.

“It became the hit of the conference, and it wasn’t even a conference event,” says Woods of the exhibit. “It was just held in conjunction with the timing of the event, which is held by quilters from all over Canada who get together. And the reaction was really great.

“That was a real transformation, because now the idea of being able to convert your history into quilt form was now fully entrenched.”

For Woods, it’s been a great joy to see an ancient craft retooled for modern purposes, in a vibrant, tactile form, and to see interest in it take root with a public that can not only marvel at the quilters’ skill and vision, but learn from them as well.

“That transformation is quite moving. Especially since a lot of these are older women, we have quilters from ages 32 to 88. So they’ve been re-energized and reinvigorated by this new set of works, and the reaction to them.”