Former Chicago Cubs relief pitcher Antonio Alfonseca’s supernumerary fingers are like tiny extra pinkies. Because they didn’t touch the ball, they didn’t give his curveballs any real edge. “Pulpo” was his nickname, Spanish for octopus.

Former Bond girl Gemma Arterton’s extra finger was more soft and floppy, with no bone. “My little oddity,” as the British actress fondly described her sixth finger, was removed when she was a child, tied off like an umbilical cord with string until it shrivelled up and fell off.

About one in 500 children are born with more than five fingers. One rarely sees them though, because the extra digits are generally considered a malformation and not terribly advantageous. So, they are lopped off shortly after birth.

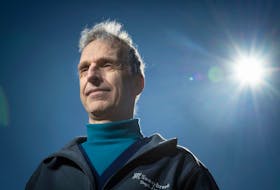

Etienne Burdet and his colleagues were not entirely convinced of the non-essential nature of the extra digits.

They recently set out to understand whether the human brain can control more than the usual body (the answer, they would discover, is yes), whether this could lead to richer behaviour (yes again) and whether, instead of sharing the same muscles as the other fingers, the additional fingers have their own dedicated muscles, nerves and brain resources (they do).

In fact, the formidable supernumerary finger on each right hand of the two subjects Burdet and colleagues recently studied gave them “exceptional manipulation abilities” compared to the normal-bodied — so much so that the researchers mused whether there might be some benefit to augmenting normal five-fingered hands with an artificial finger.

“Naively, one could imagine that in X-number of years, the six-fingered hands would provide an evolutionary advantage, and so be spread genetically,” Burdet, a professor of robotics at Imperial College London, said in an email. “However, it is likely that some ‘genetic pressure’ would keep the five-fingers design.”

Burdet was senior author of a paper published last summer in the journal Nature Communication on humans with six-fingered hands, otherwise known as polydactyly, or the presence of one or more extra digits.

The case study involved a 52-year-old woman and her 17-year-old son, each born with a fully formed extra finger between the thumb and forefinger on each hand.

“We wanted to know if the subjects have motor skills that go beyond people with five fingers and how the brain is able to control the additional degrees of freedom,” first author Dr. Carsten Mehring, of the University of Freiburg, said in a release at the time.

Indeed, mother and son could carry out with one hand tasks normally requiring two — tying their shoes, playing a complex video game at increasing speeds. “In fact, the experiments we designed (before seeing them) were too simple for them,” Burdet said. In addition to the shoe tying, other “movement” tasks included flipping the pages of a book using one hand only, folding a napkin into a specific shape and in a specific sequence using both hands and rolling towels into cylinders.

“The results demonstrate that a body with significantly more degrees-of-freedom can be controlled by the human nervous system without causing motor deficits” elsewhere, the authors reported.

Polydactyly can be traced back at least 1,000 years. Archaeological evidence exists of polydactyly individuals in Mesoamerican civilizations, and the genes behind the genetic blip have recently been identified.

Scientists know of two main types: a finger between the thumb and index finger, and a finger after the pinky, which seems to be more common but less advantageous. More rarely are people born with an extra thumb, but they can also be born with extra toes, like the mother-and-son duo studied (sometimes a bone is present, but other times it’s just a skin tag). The name comes from the Greek poly (meaning many) and dactylos (finger).

They have more ways to solve tasks than normal

In the Nature Communications paper, the extra fingers had three phalanges, or bones, and a saddle joint similar to that of a normal thumb. And, like the thumb, it moved completely independently from the other fingers. They had no trouble controlling it or coordinating its movement with the other fingers. There were also no obvious signs of any motor or cognitive disadvantages, Burdet said. It appears the brain didn’t have to borrow from other resources. The motor cortex that controls movement adapted, and grew an extra neural pathway.

Although an extra finger may not always be so functional, polydactyly people “should be proud of their superior abilities,” he said, and parents shouldn’t fret that children born with extra fingers are different.

“They have more ways to solve tasks than normal,” Burdet said. “For our subjects, at least, it also doesn’t seem to impede their sensorimotor control elsewhere.”

The findings might also help move the development of robotic extra limbs, the researchers said, because it’s the first to suggest that the human nervous system is able to seamlessly embody and integrate multiple extra appendages.

Burdet couldn’t divulge much about the mother and son. They must keep their identities anonymous. “But they are definitely proud of this special condition.”

According to Guinness World Records, the most fingers and toes on a living person is 28, belonging to Devendra Suthar, a carpenter in India. He has 14 fingers and 14 toes. He works mostly with a saw and hammer. “I have to always be careful to avoid the fingers,” he has said.

Copyright Postmedia Network Inc., 2020