After the remains of the roast beef supper were cleared from the folding tables at the community hall in Truemanville last fall, the Cumberland County Federation of Agriculture passed a motion that had been three hard years in the making.

No news outlets were at the meeting and the three blueberry growers present likely weren’t aware of the power they yielded that night when they, with the support of other farmers, passed a motion asking for an investigation into potential collusion in the blueberry industry.

Then at the Nov. 30 meeting of the Nova Scotia Federation of Agriculture that motion came to the floor. The word “collusion” was replaced with “pricing practices” and the motion was passed.

That didn’t make the news either.

Until last week when the Northeastern New Brunswick Wild Blueberry Growers Association announced it had learned the federal Competition Bureau was investigating the blueberry industry in the Maritimes.

“The Competition Bureau is investigating an allegation of anti-competitive conduct contrary to the Competition Act in the wild blueberry industry,” Veronique Aupry told The Chronicle Herald in a written statement.

“More specifically, the bureau is investigating allegations contrary to the conspiracy provision. The conspiracy provision relates to prohibited agreements or arrangement between or among competitors.”

That came as a surprise to everyone, including Oxford Frozen Foods.

“All we know is what we have seen in the media,” said Jordan Burkhardt, spokesman for the company.

“We have not been contacted by the Competition Bureau.”

With over 400 employees at its Oxford plant, the company is Cumberland County’s largest employer and the world’s largest grower and exporter of wild blueberries. It also operates plants and fields in New Brunswick and Maine.

Some local, independent growers are accusing the company of using its near monopoly in Atlantic Canada to keep prices paid for wild blueberries down.

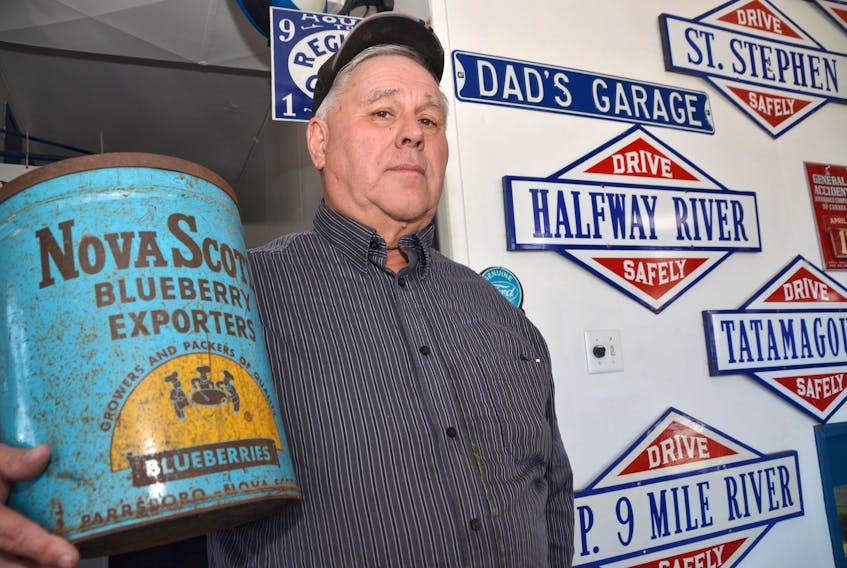

Ted Durning is one those growers.

“All the buyers are offering the same price and then you look at what you pay for them in the grocery store,” said Durning.

On Friday, a 1.3-pound bag of frozen blueberries was selling for $3.99 at Scott’s Your Independent Grocer just down the road from Oxford Frozen Foods’ plant.

Durning got 22.5 cents a pound for his berries in 2017 – a third of what he estimates he needs to make to be profitable.

Durning sells through the Cross Roads Co-operative outside Parrsboro.

Rather than going just up the road, that co-op sells its berries to a company in Maine and one in Prince Edward Island.

While covering the vastly higher trucking expenses, the two companies offer to pay its growers each year nearly the same as what is offered by Oxford Frozen Foods.

According to the Acadia Blueberry Price Report, an industry publication, Wyman’s of Maine paid growers a base price of 45 cents a pound last year in its home state. Most also received an additional six cents a pound bonus.

Its Canadian subsidiary, Wyman’s of P.E.I., meanwhile, paid the Cross Roads Co-op 22 cents a pound for Canadian berries.

Related: Wyman’s CEO denies price fixing

Oxford Frozen Foods’ subsidiary Cherryfield Foods Inc., meanwhile, paid 24 cents a pound Canadian to Maine growers.

“We are now hearing solid speculation that Cherryfield will make a further payment to Maine growers for the 2017 crop,” reads the recently released report.

“The U.S. $0.16 Cherryfield-Wymans grower price gap is unprecedented.”

Allegations of price fixing have a history in the blueberry industry.

In 2003, some 500 American blueberry growers won a class action lawsuit against Cherryfield and two other Maine processors for price fixing.

The Chronicle Herald spoke with multiple Nova Scotia growers who point to processors from Maine and Prince Edward island price matching Oxford on its home turf while offering more elsewhere for blueberries as evidence of collusion.

It’s an allegation flatly denied by Oxford Frozen Foods.

“Certainly we do not engage in any price fixing behaviour,” said Burkhardt on Friday.

And according to Daniel Campbell, the Competition Act requires more evidence than just price comparisons.

“They have to show these people talked to each other and were doing something to create an agreement,” said the Halifax-based lawyer with expertise in competition law.

That is a tall order.

The investigation into bread price fixing among Canada’s top retailers and bakeries only began after Loblaws and George Weston voluntarily went to the Competition Bureau, admitted participating in it and named other companies.

They received immunity from prosecution in exchange.

“(The blueberry industry investigation) is a little unusual – usually it’s the guys who sell the produce who are fixing the price,” said Campbell.

“This (allegation is against) the guys who are buying the product.”

The Competition Bureau has broad police-like powers to investigate.

“They sometimes simultaneously go into offices of all the competitors and seize their computers,” said Campbell.

He cautioned against reading too much into the existence of an investigation. He said the bureau is required by law to investigate anytime a group of five or more citizens file a complaint, regardless of its merits.

The Competition Bureau wouldn’t provide any more details on the extent of its investigation so far, though The Chronicle Herald was able to confirm that it has contacted industry players for pricing information.

Unless charges are laid against someone, we may never know any more than we do now.

And that’s not very much.

In Parrsboro, blueberries were the talk at CE Sargent and Son Ltd.

“There’s an oversupply of blueberries,” said Art Sargent, owner of both the Ford outlet and 700 acres of Cumberland County blueberry fields.

“Oxford has been buying berries that it shouldn’t have been buying to help the farmers. It’s supply and demand.”

Three years of bumper crops have resulted in hundreds of millions of pounds of blueberries in industry cold storages, including those belonging to Oxford Frozen Foods.

David Yardborough doesn’t think it’s a case of price fixing by processors.

“I think the issue is that there is a huge glut of blueberries on the market,” said the blueberry specialist at the University of Maine extension office.

“The price is the price.”

Durning cleared the majority of his fields with a chainsaw, hired excavators to pull stumps and invested in encouraging the low growing vines.

“I did it slowly – getting one field finished and paid off before I bought another property. I was always afraid of debt,” said Durning, 74.

“Those fields were supposed to be my pension.”

With price predictions not looking that much better for 2018 and the knowledge that American growers are getting more, suspicions weigh heavily on blueberry growers.

Amongst the acidic hills and abandoned farms where the Cobequid Hills march down to the Bay of Fundy, Durning’s generation grew up painfully aware that opportunity was created, not found.

And now the opportunity they created for themselves is not looking so bright.

For his part, Sargent started rhyming off processors that have gone belly up over the past 60 years.

“MacLean’s in Springhill, that company in Shediac, Mega Bleu, Kolby Foods, Nova Scotia Blueberry Exporters – they were all companies that you used to be able to sell berries to who tried and failed,” said Sargent.

“We made quite a bit of money over the years, but this is a tough business. You have to be strong to stay in it.”

It’s that toughness shown by Oxford that has made for some strained relationships in a cash-strapped county with long memories and no greater export than blueberries.

Walking in Sargent’s door on Thursday afternoon was Frank Quinn.

“Here comes a guy with an opinion different than mine,” said Sargent.

The president of the Crossroads Blueberry Co-op had bought a car from Sargent last week.

“Years ago, John Bragg came to the co-op and said ‘Sell me all your berries or I won’t buy anymore from you,’” said Quinn.

“Some felt that wasn’t fair so we haven’t sold to him since.”